Scott R Jones

(3 comments, 20 posts)

This user hasn't shared any profile information

Posts by Scott R Jones

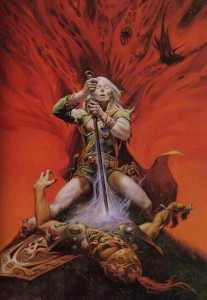

Cold Blades and Cosmic Blasphemy!: A Review of “Sword and Mythos”

1Though I grew up in the era that saw the rise of Dungeons&Dragons as a cultural touchstone, I was largely clueless about the genre it drew most if not all of its cues from. An example: I had no idea what those kids were playing when I saw E.T.: The Extraterrestrial as a boy.

I thought it was some kind of club meeting or something, and wondered when the spaceships were gonna show up. (I suppose it was a club meeting, after a fashion. And I was always waiting for spaceships to show up, anywhere.) This remained the trend into my teens: I was more into Heinlein than Hickman, more Bradbury than Brooks, more PKD than Piers Anthony.

When I did finally get into Sword & Sorcery, it was only through the British New Wave, and the work of Michael Moorcock, especially…

And back from there, to Fritz Lieber’s Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser stories, to REH and Conan, and finally to Clark Ashton Smith, who I was learning about at the same time I was first encountering HPL. And even then, I burned out on Sword & Sorcery early, finding the majority of the stuff (aside from the greats already mentioned) to be derivative and dull. It’s a genre of necessarily broad strokes, easily becoming a parody of itself.

So, I was prepared to be underwhelmed by Sword & Mythos, the new anthology from Innsmouth Free Press that melds S&S with the cosmic beasties and themes of HPLs world and worldview. The Cthulhu Mythos is itself a genre (or a thematic idea that attaches itself to genres, leech-like) that crumbles into pastiche in less-than-sensitive hands.

So, I was prepared to be underwhelmed by Sword & Mythos, the new anthology from Innsmouth Free Press that melds S&S with the cosmic beasties and themes of HPLs world and worldview. The Cthulhu Mythos is itself a genre (or a thematic idea that attaches itself to genres, leech-like) that crumbles into pastiche in less-than-sensitive hands.

Thankfully, the diverse hands at work here are sensitive indeed, and editors Moreno-Garcia and Stiles have collected stories that are thoughtful, energetic, creative fusions that are (with one exception) a joy to read, and I’m happy to report there’s not a blonde-headed reaver of the standard S&S type anywhere.

Locales and times visited here range from Africa (Maurice Broaddus’ The Iron Hut and Thana Niveau’s The Call of the Dreaming Moon), ancient Palestine (Ed Erdelac’s incredibly muscular and horrific The Wood of Ephraim), primal Mesoamerica (Nelly Geraldine Garcia-Rosas’ creepy In Xochitl In Cuicatl In Shub-Niggurath), the island nations of Java (Nadia Bulkin’s regal Truth is Order and Order is Truth), and imperial China (the tone-perfect and truly excellent The Sorrow of Qingfeng by Grey Yuen), to more mythic zones: Arthur’s Britain (Adrian Chamberlin’s The Serpents of Albion), the Carcosa of Chambers (Sun Sorrow by Paul Jessup), and an interdimensional hell-realm ruled over by an avatar of Nyarlathotep (E. Catherine Tobler’s And After the Fire, A Still Small Voice).

This latter tale was a standout for me, and a good example of what makes Sword & Mythos such a good collection: Tobler’s heroine here is someone familiar to readers who know their history, and the tragic nature of her plight, and the nuanced way Tobler hints at her identity and reveals her character through the narrative is masterful. (I won’t spoil the reveal.) This mastery is on display in most every selection here, whether it’s used in the service of humourous broad-chested bombast (Balogun Ojetade’s Black Caesar: The Stone Ship Rises), revealing the terrible costs of sorcerous contracts (Spirit Forms of the Sea by Bogi Takács), or cleverly deconstructing the Mars of Edgar Rice Burroughs (Jon Carver of Barzoon, You Misunderstood by Graham J. Darling) and fairy-tale tropes (Orrin Grey‘s little gem, The Bones of Heroes). Each author’s mash-up of the genres is fresh and interesting, and their characters are anything but cookie-cutter Conans. There are plenty of strong women (I do not mean the execrable Strong Female Character), fully eight of the fifteen tales have female protagonists; and people of every race (human and otherwise) besides. This is an anthology that attempts, and I believe succeeds, in presenting a very wide world to the reader. “Myopic” is one thing Sword & Mythos is not, which is incredible, considering the subject matter.

The only exception to this rule, in my reading, was an irritating tale by the prolific William Meikle, No Sleep for the Just. This featured a sentient blade and its English master/slave versus a fairly standard Dagon cult. I’ve enjoyed Meikle’s stuff elsewhere, but here he employs a stylistic tic of italicizing certain words again and again (the sword is constantly thrumming, there are fish, and things, and so on), an amateurish effect that pulled me right out of the story. Maybe it’s my early exposure to the cult of Moorcock, but the living sword here could have been done so much better, as it is in the other, superior tale here, Jessup’s Sun Sorrow. Diana L. Paxson’s Light was similarly clunky, but I put that down to the modern day setting (an archaeologists dig, manned by at least two SCA members, possibly more, and referencing that organization at least once) meshing poorly with elder Norse mythology more than anything else, and it is nowhere near as grating as Meikle’s entry.

Sword & Mythos finishes up with a quintet of short essays on the literary underpinnings, historical and otherwise, of both genres. Highlights here are G. W. Thomas and his Conan and the Cthulhu Mythos (a nice breakdown of the partnership-on-the-page of REH and HPL); editor Paula R. Stiles marks out the fine lines of the genre in What’s So Great About Sword and Planet?; and editor Silvia Moreno-Garcia has some fun with the Mexican comic-books of her youth in Spanish Conan: Manos, Guerrero Indomito.

Another great anthology from Innsmouth Free Press, easily one of the best small presses out there. Recommended. You can purchase the print edition directly from IFP and the title is also available in e-book formats (I strongly urge you to go print on this one: as with all IFP titles, it’s a very nicely put together book.)

Scott R Jones is the author of the short story collections Soft from All the Blood and The Ecdysiasts, as well as the non-fiction When the Stars Are Right: Towards An Authentic R’lyehian Spirituality. His poetry and prose have appeared in Innsmouth Magazine, Cthulhu Haiku II, Broken City Mag, and upcoming in Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine.

Scott R Jones is the author of the short story collections Soft from All the Blood and The Ecdysiasts, as well as the non-fiction When the Stars Are Right: Towards An Authentic R’lyehian Spirituality. His poetry and prose have appeared in Innsmouth Magazine, Cthulhu Haiku II, Broken City Mag, and upcoming in Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine.

Cosmic Claustrophobia: Gabriel Blackwell’s ‘The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised-Men’

1Part of the appeal of H. P. Lovecraft’s work is the sensed worlds (of teeming monstrous biology, creeping paranoia, undeniable nihilism) that lurk not so much within the text itself (famously verbose and weighted with archaisms as it is) but in the spaces between the flowery words and behind the formal lines. Lovecraft’s fiction is all about the suggestion, the hint, and that which we speak of when we speak of the unspeakable. To read Lovecraft is, in a lot of ways, to get what the man was about, under his surface veneer of genteel literary gentleman and scion of a decaying New England family. Under all that, well… horrors abound. Potent fears. Crippling anxieties.

All of which goes a long way to explain his continuing popularity well into the 21st Century, while the other, more successful pulp writers of his own time are all but lost to obscurity. Lovecraft somehow speaks to the current human condition. This is the Age of Crippling Anxiety, and Lovecraft is fast becoming its patron saint.

Gabriel Blackwell’s The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised-Men (Civil Coping Mechanisms Press) taps into that pervasive feeling of alienation and helplessness that bleeds out crimson between HPL’s purple prose and infects the reader. And the manner in which Blackwell does it!

Gabriel Blackwell’s The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised-Men (Civil Coping Mechanisms Press) taps into that pervasive feeling of alienation and helplessness that bleeds out crimson between HPL’s purple prose and infects the reader. And the manner in which Blackwell does it!

Here are the bare bones of the plot: Lovecraft did not die of a combination of bowel cancer and Bright’s Disease. Or rather, he did, but the illness was merely a symptom (and not the only one) of a foul existential contagion transmitted to him through a textual artefact, a letter from a deranged fan resident in an asylum. And the name of this secret priest of the Great Old Ones? Gabriel Blackwell.

Natural Dissolution… is the record of the author (the present-day Gabriel Blackwell) travelling to Providence to search for his vanished girlfriend (who may or may not actually exist), where he finds temporary work shredding old hospital documents. Among these he finds HPL’s file, and within that, he finds Lovecraft’s final hand-written letter to his fan/persecutor/killer, which details the effects of that Blackwell’s (no relation? Maybe. Maybe not…) letter to him, and the rapid slide into hallucination, madness, and disease it triggered in him. Effects which, as the author Blackwell soon learns during his own descent into madness, continue to transmit through Lovecraft’s own letter.

There are some marvelously descriptive passages in Natural Dissolution…, passages that deliver on the fevered promise of both Lovecraft’s fiction and psychedelic use: if we could only look deep enough into things, then all would be revealed. It’s William Blake’s doors of perception getting busted wide-open, only to reveal, not a spacious and infinite universe of light and reason, but a claustrophobic infinite regression of fractal foulness, mutating forms, and crushing psychological darkness. Lovecraft, who only thought he saw the truth at the bottom of things, finally sees it, and it kills him. Blackwell, who only wants to find his girlfriend, instead finds a twisted passage (through the transcription and translation of the letter) into the emptiness of his own existence. The final chapters, with his return to the West Coast (divested of the letter by a thoroughly Lovecraftian trope: the jostle/mugging by a dark stranger in an alleyway near the piers) and the half-life he left there, give the reader a final maddening coda: Gabriel Blackwell the Author is perhaps host to the personality of Gabriel Blackwell the Lovecraft correspondent, and evidence of another person or entity living in the apartment he rents (and has filled with hoarded material to become a maze-like mirror of his psyche) hints that doors through time and mind have been opened and will never shut.

That being said, Natural Dissolution is also funny as hell. There’s a real David Foster-Wallace feel to the narrative, a dry humour in the sorting of awful phenomena and altered perceptions. Much of the story is pieced together through footnotes, and footnotes to footnotes, reminding me of House of Leaves, but in a good way. And Blackwell hits the perfect tone for Lovecraft’s voice: plummy and self-assured at points, devolving into “my god, that hand! The window! The window!” fevered hysteria at others, but sympathetic at all times. It’s Lovecraft’s last letter, and it feels just so, which is an amazing accomplishment.

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised-Men is far and away one of the better literary horror novels I’ve read. Witty, urbane, deranged and ultimately very unsettling. Highly recommended.

Scott R Jones is the author of the short story collections Soft from All the Blood and The Ecdysiasts, as well as the non-fiction When the Stars Are Right: Towards An Authentic R’lyehian Spirituality. His poetry and prose have appeared in Innsmouth Magazine, Cthulhu Haiku II, Broken City Mag, and upcoming in Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine.

Scott R Jones is the author of the short story collections Soft from All the Blood and The Ecdysiasts, as well as the non-fiction When the Stars Are Right: Towards An Authentic R’lyehian Spirituality. His poetry and prose have appeared in Innsmouth Magazine, Cthulhu Haiku II, Broken City Mag, and upcoming in Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine.

Bending, Curving, Humming Cosmic: Bryan Thao Worra’s Sublime DEMONSTRA

1If there’s a problem with genre fiction at all (and particularly the horror genre, and even more particularly Lovecraftian genre fiction – OK, multiple problems, I know, I know), it’s that its writers have an unfortunate tendency to bog down in the minutia of the form and format, resulting in stories which merely rehash the already fragrant pulped material of previous years. And so we end up with protags going for a drink down at Tcho-Tcho’s Bar & Grill, or yet another shuddersome “Check it! The Yellow Sign!” and so on. I highlight Lovecraftian tropes here (because that’s my eldritch bailey-wick) but this same issue can and does appear anywhere in genre material: we all know what to expect from zombies, vampires, Little Green Men, and the like, and most toilers in the genre vineyards see little reason to break from those tried-and-true molds.

That’s prose, and such laziness can in most cases be forgiven. There’s only ever one Story, after all, or at most a dozen, so more repetition than reinterpretation/rehabilitation can be expected, even tolerated.

Unlike mere story, though, each poem is (or should be) unique, and when the above happens in poetry, and particularly poetry in the speculative fiction arena, the results are disastrous: lame re-treadings of sci-fi or horror tropes, humourous barely-a-poem asides loaded with references for the in-crowd, and no examination of wider themes relating to the poet’s world or indeed, the world outside that world. This is why (with the exception of Ann K. Schwader) I’ve steered clear of reading “horror poetry”: it is largely a shallow dip into a mostly empty interior geek-space, the space of the specific subject of the poem (zombies, extra-dimensional beast-gods, whatever) and it has nothing to say to me. With a poem like that, once read there’s just no good reason to re-read, and that, for me, is what characterizes a decent piece of poetry, the urge to return and begin again. So why start?

Well, on several recommendations I bought and started Bryan Thao Worra’s DEMONSTRA. I read it straight through in one sitting, and have since read it several times more, in whole or in part. DEMONSTRA is clever, insightful, compassionate, often funny, sublime. Worra brings a very human eye to the world he sees, and that world is filled with, yes, Lovecraftian critters and deities, rampaging kai-ju, giant robots, and the occasional zombie, but also the cultural warping of the Lao diaspora, the god-forms and spirit beings of Laotian belief systems, wrestling sages, surreal road trips, and the meathook realities of wars public, secret, and internal.

Well, on several recommendations I bought and started Bryan Thao Worra’s DEMONSTRA. I read it straight through in one sitting, and have since read it several times more, in whole or in part. DEMONSTRA is clever, insightful, compassionate, often funny, sublime. Worra brings a very human eye to the world he sees, and that world is filled with, yes, Lovecraftian critters and deities, rampaging kai-ju, giant robots, and the occasional zombie, but also the cultural warping of the Lao diaspora, the god-forms and spirit beings of Laotian belief systems, wrestling sages, surreal road trips, and the meathook realities of wars public, secret, and internal.

Only two pieces into DEMONSTRA, there is a poem about the Deep Ones. Now, there are only so many places a poet can go with Lovecraft’s batrachian breeders from below, right? Worra doesn’t go to any of those places and the result is a poem of peculiar melancholy and spiritual intensity. A line:

Bending, curving, humming cosmic.

Awake and alien.

That is as good a definition as any of what great poetry actually is: the written word used as a hyperspatial bridge to another, radically different point of view, an eyes-wide-open felt experience of ourselves as not-ourselves, which yet comes round again, bending, curving, to speak to our centre: great poetry is a humming transmutation device for the soul. And that is what Worra’s writing in DEMONSTRA does, piece after piece.

Some highlights were Zombuddha (a striking comparison of the traditional Western zombie with the rough lineaments of enlightenment that made me laugh out loud with the pleasure of recognition “Yes! Of course!”); the rich re-telling of Call of Cthulhu from a Lao perspective in The Terror in Teak; the epic road poem The Dream Highway of Ms. Manivongsa (“Fifty years from now, no one will see any difference / Between J.R. and J.F.K., or who shot them. / Now, flee.”); and Full Metal Hanoumane, which includes a geeky reference to Planet of the Apes, true, something that in lesser hands would make a clanging mess of the poem, but here transforms it into a clear bell tolling in the purple depths of space.

Worra has mastered his subjects, instead of the other way around. He has, over four previous books and multiple publications, also mastered his poetry, and I suspect he has mastered his self, his own “writer’s ego”, to a degree that allows him to enter his interior world, return with jewels that reflect that world and ours, and then place those jewels in perfectly appropriate settings that only add to their lustre. I highly recommend this book: it is a bright spot in the overwrought gloom of standard speculative/horror poetry and well worth acquainting yourself with. The appendices: of Lao spirit-entities, and Cthulhu Mythos deity-names translated into Lao; as well as the lovely artwork of Vongduane Manivong that grace the pages, are an added bonus.

DEMONSTRA is published by Innsmouth Free Press, a Canadian micro-publisher of weird and truly wonderful work. You can order DEMONSTRA from them directly here. Bryan Thao Worra can be found here and followed on Twitter @thaoworra